Between Word and Meaning, Part III

“Sweep everything under the rug long enough, and you have to move right out of the house.” - Rachel Ingalls

It’s been a bit since I’ve written, so I’ll quickly summarize: I’ve discussed how Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home changed my life as it held up a (thematic) mirror to reflect my own experiences in life growing up with an alcoholic parent. It revealed to me how we often and unknowingly separate the concept of truth into two distinct ideas: factual truth and experiential truth. I firmly believe that people tend to hold experiential truth in higher regard to factual truth. And that’s a big problem. It turns truth itself into a response to the vibes. If something feels like it could be true… well, most people then decide it is.

And that’s a big problem.

Bechdel uses literary allusions throughout Fun Home as evidentiary pieces of a puzzle. She uses the term “suggestive circumstances” as clues that point to other clues that reveal additional hidden clues in the search for truth.

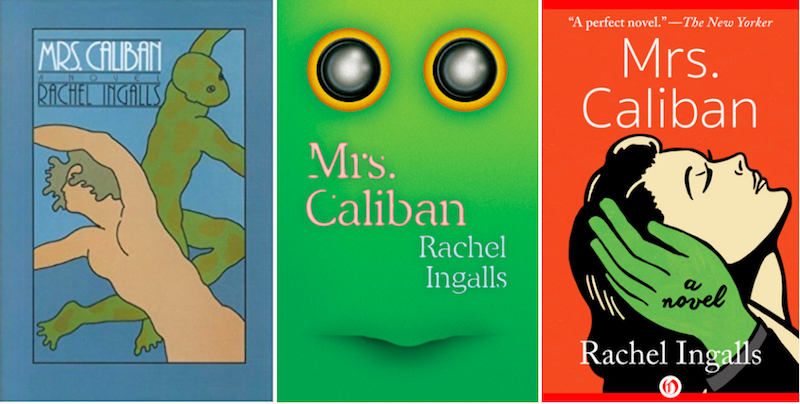

There’s a novella by the name of “Mrs. Caliban” by Rachel Ingalls I’d like to introduce into evidence.

“Mrs. Caliban” is the story of Dorthy and her affair with a half-man, half-amphibian creature named Larry. (This predates Guillermo Del Toro’s “The Shape of Water” by a few decades. But also, “The Creature from the Black Lagoon” existed before it.)

Dorothy is a housewife whose husband Fred has had a few casual dalliances. Their infant son died and they have also experienced a stillbirth. Dorothy - not only in the home, but also in her experiences with her neighbors and community - feels unseen, unheard, unknown, and uncared for. She is portrayed as a woman not so much lost in grief as utterly surrounded by it and captured by it: grief for what has been lost, grief for her dead marriage, grief for her dead life, and grief for a future as unchanging as the present she is living.

One day, a hulking creature appears in her kitchen (the radio playing had just recently played a news item about a recently-escaped… thing… from a nearby research lab) and introduces himself/itself as Larry. Dorothy’s monochrome existence is suddenly filled with color (think “Pleasantville”): she has someone to talk to, to show interest in her, to laugh with. To use the word and all its definitions: she becomes intimate with Larry.

It’s not just about that, though. Larry becomes mothered by Dorothy who now gets to mother someone. She finally has a dependent. She protects Larry and keeps him safe from discovery. She provides him shelter and nourishes him with food and love. Larry also possesses a childlike naivete that Dorothy is charmed by; she provides him instruction and helps mature him to society’s ways and norms.

This not only changes who Dorothy is but how she is. Where once she clung to the very shadow of her husband Fred while taking his affairs as par for the course, she slowly begins to view him with contempt and finds no value in his opinion of her. With her neighbors, conversations she once longed to have no longer provide her with any kind of connection. She views her neighbors with pity; not having the type of relationship she shares with Larry and not possessing the kind of secret (again, Larry) she has. Their opinions of themselves, of their lives, and especially of her and her life begin to also mean nothing to her.

Larry helps Dorothy become who she was all along - for better or worse.

I bring up this book because there’s a detail worth mentioning: there is no evidence in the world of the book that Larry even exists! The reader only has Dorothy’s point-of-view. We have no choice but to believe he is real. But, other than news reports that a creature has gotten loose from a lab, there is no other evidence whatsoever that Larry is even that creature or that he actually exists in the reality of the book. Dorothy hides him so well that no one sees him. No one questions her about… anything. There aren’t any clues left by Larry or Dorothy that he’s present in the home she shares with Fred. He suspects nothing. No one does.

I want to argue, though, that Larry’s existence ultimately doesn’t matter. What matters most is Dorothy believes he exists. That is fundamental: she believes and accepts it as truth. Ingalls put so much ambiguity into the story and there’s been much literary discussion about Larry’s actual existence. But it doesn’t really matter! Dorothy believes he’s real and shapes her behaviors around this belief. That’s what matters!

We ultimately don’t really care if facts inform the truth by which we live and use to shape our lives. Experiential truth - especially when factual truth is contradictory - is just so damn convenient, isn’t it? The vibes just gotta be pristine!

That right there is the crux of my thesis about all this. Maybe I buried the lede, but… Sometimes writers do that, yeah? And writers are human and humans love to hide shit. And not always on purpose. The more I let my mind wander while I write, the more I understand when writers say the story just flowed from them or they let the characters reveal the story. Like… maybe a little bit bullshit, but maybe completely accurate, as well?

So yeah, the point in all that I have written and will write about myself, Fun Home, and anything/everything else in this series of posts is this: it took a book to validate my experience, to help me see our performances of normalcy (especially in the contexts of family relationships and trauma), to help acknowledge the hidden realities we create, and just how much value we collectively place on “the truth” (hint: not a lot, actually).

That right there is the power of literature. That is why reading is fundamental. It is vital. In fiction, we are given the tools of self-understanding, to discover human nature, to build empathy, to challenge preconceived notions, to shake us wide awake. It only took one book. And what’s even more powerful is that a zillion other people could read Fun Home and walk away with totally different ideas and conclusions.

Ah, literature.

Yeah, we’re entertained along the way. But that’s the trick writers play on you. You laugh, you cry, you bite your nails, you get a little hot under the collar. But you also learn. About yourself, about your community, about others, about communities and places and worlds you’ll never go to or experience.

And you become all the better for it. More whole.

More you.

And more later. Until next time, folks!