Between Word and Meaning, Part II

“Was Daedalus really stricken with grief when Icarus fell into the sea? Or just disappointed by the design failure?” - Alison Bechdel

Content warning: suicide

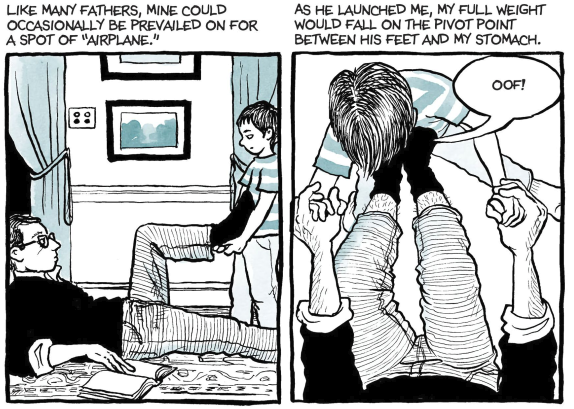

Bechdel opens Fun Home with a recollection of a “spot of ‘airplane’” played between her and her father. She then relates to the reader that acrobatic acts in the circus that mimic the airplane maneuver are called “icarian games”. She continues: “In our particular reenactment of this mythic relationship, it was not me but my father who was to plummet from the sky.”

We’ve all had those moments where our parents seemingly crash to earth before our very eyes; where these mythical beings - not quite God, but gods all the same - somehow lessen and become what they’ve always been: just human. It’s the glimpse behind the curtain. Having to acknowledge to yourself that the wizard is actually just some dude trying to get through the day.

This… flattening… of a 3D character to 2D dimensions… It’s rough. It’s enlightening. And it’s a lot to reconcile. How to make the gears fit with one another: of practically needing a god-like figure in your life and knowing they’re simply human - not unwilling to fill a role, but incapable.

Also important is when this crash to earth occurs in the life of both the child and the parent. For Bechdel, it happened just months before her father, Bruce, died.

For me, it was long before my own father’s death.

Bechdel likens her father to both Icarus (crashing down to earth) and Daedalus, “that skillful artificer”. Admitting that “I employ these [literary] allusions… not only as descriptive devices, but because my parents are most real to me in fictional terms.”

We are all practitioners of artifice in one way or another, though, right? If you grew up with an alcoholic parent, like I did (my father, in this case), you become an adept architect in artifice.

First, you lie to yourself. That what you are experiencing is fine and normal. Then, you lie to your family. That what you are experiencing is fine and normal. Then, you lie to the alcoholic parent. That what they are making you experience is fine and normal. And finally, to the world at-large: that you are fine and normal.

She writes that he “used his skillful artifice not to make things, but to make things appear to be what they were not. He appeared to be an ideal husband and father, for example. But would an ideal husband and father have sex with teenage boys?”

Bechdel learned of her father’s closeted homosexuality as an adult. She came out as a lesbian to her parents via letter four months before her father’s death. She received a phone call from her mother“in which she dealt a staggering blow. ‘Your father has had affairs. With other men.’” She tells how she felt “upstaged, demoted from protagonist in my own drama to comic relief in my parent’s tragedy.”

That’s a bit how I felt growing up with an alcoholic father. That, rather than being encouraged to live a life of my own on my own terms, I was instead expected to play a supporting role in upholding the lie my father was living. Because even though the alcoholic often operates in public, it is in (relatively speaking) private that they - and their family - suffer. Often, alcoholism is a manifestation of unresolved trauma. So the appearance of normalcy becomes an act. And in order for the normalcy act to be successful, the entire family not only has to buy-in to the lie of normalcy, they must also then play their part.

And I stopped playing my part pretty early.

Like Bechdel, I want to avoid the temptation “to suggest, in retrospect, that our family was a sham.” The outward appearance of our happiness certainly was (early on it was simply an appearance put on by nothing more than sheer ignorance), but the love we felt for each other absolutely was real. It was tangible. It was fierce. Sure, maybe my sisters and I were a little more trauma-bonded than normal, but there were so many times it unequivocally felt as if it was us three versus the world. No one experienced our lives the way we did. Hell, we argue - fight and become estranged! - over our recollections and interpretations of the same damn events we experienced. That’s life, though, right? In all its abnormal, ugly, agonising normalcy.

I ache with deep empathy when I read Bechdel’s words: “His absence resonated retroactively, echoing back through all the time I knew him… He really was there all those years, a flesh-and-blood presence… But I ached as if he were already gone.”

In a sense, I lost my father twice: once to alcohol before I was even born, and then again when he died. But I had been estranged from him for the better part of a decade when he died… and a few other times throughout my adult life. I guess, if you really think about it, with the estrangements and reconciliations and additional estrangements and then him falling off the wagon and (allegedly) getting better and the apologies and the apologies and even finding myself apologizing to him for his behavior… I lost my father over and over again. Each time he’d return he’d be a little more distant; I would feel a little more ostracized. I was expected to fulfill a certain role, but the entire act became burdensome. I didn’t just refuse to play my lines, I refused to star in the entire damn show.

Bechdel says with certainty that her father killed himself. And yet, she admits, there is no proof to grant her this certainty. Instead, she says there are “suggestive circumstances.”

And this is where I really fell in love with what this book is about: how we reconcile factual truth with experiential truth; wrestling with them and eventually giving only one of them preferential treatment in our lives.

For me, having experienced what I had in my life, it brought a moment of clarity. Like Oppenheimer staring at the blinding nuclear explosion, a light had illuminated my life. What is truth without facts? How can we even begin to define that? Why do we even define something as true when there is no supporting evidence? What conditions and conditioning lead us to behave this way?

Growing up with an alcoholic parent, you begin to juggle these questions and these dualities far long before you are able to even articulate them. You settle in a rhythm where what is doesn’t matter as much as what was say is, is. In other words, what one feels to be true is far more important than what is factually true.

I hope that makes sense. And I hope that in future installments of this I will be able to clarify. If anything’s clear right now, it’s that I have no sense of direction for this little project, but I definitely have a destination: hopefully a thorough examination of our war with experiential truth and factual truth.

I also want to put it out there that I’m not writing all this to simply air out dirty laundry or anything of the kind. I just really want to share the powerful impact one book has had on my life and to show that reading is an essential skill that must be developed in everyone if we are to move forward as a society. You can read Fun Home and walk away with the idea that Alison Bechdel used the comic book art form to talk about her life and you would be 100% correct. But you can also read the book with a critical eye and let her words speak to a part of you that is ready to be spoken to. Each book has that potential. My heart’s desire is for every person to read a book that gives them that Oppenheimer-staring-at-the-sun moment.

I’m just over here sharing my heart, that’s all.